For many who are involved in Western Martial Arts (WMA), the only goal of practicing historical swordsmanship is to come as close as possible to developing real martial skill in the use of period weapons. Members of The Order of Lepanto also share this goal, but not as a means unto itself: it is a path to enhancing your faith life, preparing for spiritual warfare, and guides you in living out your vocation.

Unlike sixteenth century swordsmen, today’s student of the sword will, most likely, never have the opportunity to put his skill to the ultimate physical test. Even so, we want to develop true martial skill in the art. By then translating the lessons to our spiritual life, we will be more prepared for the real-life tests our faith will have to endure. So the approach we have developed at the Order is true to martial skills, martial heritage, and orthodox Catholic teaching. It is certainly one of the most complex, and it offers something more than what is generally available in Western swordsmanship. Let’s look at what the Order of Lepanto’s method of teaching historical swordsmanship and spiritual growth is all about.

Unlike sixteenth century swordsmen, today’s student of the sword will, most likely, never have the opportunity to put his skill to the ultimate physical test. Even so, we want to develop true martial skill in the art. By then translating the lessons to our spiritual life, we will be more prepared for the real-life tests our faith will have to endure. So the approach we have developed at the Order is true to martial skills, martial heritage, and orthodox Catholic teaching. It is certainly one of the most complex, and it offers something more than what is generally available in Western swordsmanship. Let’s look at what the Order of Lepanto’s method of teaching historical swordsmanship and spiritual growth is all about.

What’s the point?

If you’re serious about learning swordsmanship, then the measure of any system of study is the quality of the education that results. In other words, you expect a working knowledge of how to fight effectively with swords. You also want to acquire the basics within a reasonable amount of time – without the “wax on, wax off” routines that tend to keep beginners from quickly advancing. Ultimately, the system should produce a mature, competent swordsman – a swordsman capable of using real weapons in actual combat.

The farther a system gets from the reality of combat, the less useful it becomes to the student who wants true martial skill. Realistically, all systems involve a certain amount of “distance from combat reality. Simulations are used as an alternative to real fights. Safe sparring systems must be created to meet the demands of modern studies. A reasonable gage of an effective system is to see how closely its sparring system resembles the dynamics of real weapons use. This is an area where The Order of Lepanto and one other group stand out. Our sparring systems are merely a means to an end, not an end in themselves. We do not try to achieve skill at “sparring.” Rather, a number of sparring techniques are used to develop skill at fighting. You can judge the value of a sparring system by measuring how well true fighting principles work in the sparring environment. Ideally, the system should allow you to do what works without letting you get away with what wouldn’t. Target areas and sparring weapon construction are two factors which will figure in this appraisal.

If you’re serious about growing in your faith, then we would measure that system by a different standard: are you becoming more patient, are you learning to love people who are hard to love, are  you increasing your knowledge of the faith. Many people today have been left with a teenage understanding of the faith because that is where the traditional religious education program stopped. The Order of Lepanto aims to build an adult understanding of your catholic faith and help you to grow in that faith.

you increasing your knowledge of the faith. Many people today have been left with a teenage understanding of the faith because that is where the traditional religious education program stopped. The Order of Lepanto aims to build an adult understanding of your catholic faith and help you to grow in that faith.

Learning a fighting skill, like WMA, is not an invitation to random violence, as some might suggest. Rather, it is learning to discipline your body and mind to achieve a difficult goal. The building of courage, strength, decisiveness, and confidence are the fruits of the martial arts portion of The Order of Lepanto, while finding out how God wants those skills directed and used are the fruits of the spiritual component of our program. Pursuing both the physical and spiritual with equal gusto are necessary to

Determining the Focal Point

Before proceeding, let’s narrow the focus a bit. The only way to evaluate any training system properly is to first grasp its intended role in the overall goal of a program. Developing martial skill and building a healthy, Catholic faith life is the goal of our system. There are no contests or competitions. Sparring itself provides a workshop in which members can safely practice the martial skills that they’ve learned. Our faith studies then go on to provide a framework to relate that martial skill to the realities of spiritual life for the Church Militant. Comparing what The Order of Lepanto does to what a number of non-martial groups are doing with swords will help bring this point into focus.

First, we will look at sport fencing. In spite of its ancestry, modern fencing is not meant to transmit the art of historical swordsmanship. The foil, epee and saber are no longer stand-ins for weapons but ‘weapons’ themselves. In sport fencing, the value of a technique is not its lethality but its ability to score, and the attitude of the modern fencer is competitive rather than martial (a trend that can be seen in some Eastern martial arts, too). It must be said that modern fencing lays no claims to teach an historical system of swordsmanship – it’s an evolving sport where new innovation takes fencers towards the sport aspect and further from its roots.

However, things you learn from sport fencing instruction can be useful in studying historical swordsmanship. Familiarity with fencing terminology is a plus and practicing fencing is a better preparation for a real sword fight than no practice at all. But the purpose of fencing is not the study of historical swordsmanship, so the merit of the sport has little impact on our present evaluation.

A sub-culture has emerged in the fencing community which is focused on the teaching of eighteenth and nineteenth century swordsmanship. Classical fencing asks the question, “What if our swords were sharp?” Techniques and thinking of the modern fencer are removed, and the classical fencer returns to a more martial use of the dueling epee and the smallsword.

A second practice we will review is the fighting done in the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA), which they classify as “heavy” and “light”. While these forms are practiced as a kind of competitive sport by many, and as a semi-martial practice by some, their intent is not to produce swordsmen skilled in the use of real weapons. As with sport fencing, there may be many benefits afforded by SCA, but these are secondary to the main purpose of the pursuit.

The question of “purpose” or intent is critical, as you can’t fault a system that doesn’t claim to teach real swordsmanship for using a sparring system that doesn’t prepare a student for the realities of combat, much as you cannot fault a secular school for failing to teach the Catholic moral standards. While many people criticize systems like that of the SCA for these reasons, we must understand that SCA combat was never intended to be a martial pursuit.

Stage combat falls into the same category. Many stage combatants use replica weapons, and they create a spectacle which looks convincing to the untrained eye. We must remember that stage combat is about creating an illusion, not a fight. In that pursuit, stage combatants often sacrifice “authenticity” for the purposes of safety or entertainment and we shouldn’t be surprised – or concerned. People study stage combat to learn how to pretend to fight, not how to do it for real.

In summary, the exclusion of these three categories is not intended to disparage their participants or discourage their pursuit. All require skilled participation and can produce impressive results. None of them claims to teach historical swordsmanship, like The Order of Lepanto and a couple of others. But unlike other martial programs, The Order of Lepanto exists not only to preserve and pass on a practical understanding of historical swordsmanship, but to also cultivate a faith life similar to the deep religious belief of the historical swordsman himself.

The obsolescence of the sword

One factor irrevocably separates anything we do today from the historical reality: the obsolescence of the sword. No matter how proficient your skill with the sword, you’ll most likely never use it in a  life or death context. Even if the nearest thing at hand when your house is broken into is your trusty longsword, the odds of your intruder also being a swordsman are slim to none.

life or death context. Even if the nearest thing at hand when your house is broken into is your trusty longsword, the odds of your intruder also being a swordsman are slim to none.

Because people no longer use swords for real anymore, there is no common knowledge to draw upon in the study of swordsmanship. Nowadays we use guns, and even people with no formal firearms training know enough to operate the weapon. The same was most likely true in the fifteenth century with swords. The process of learning swordsmanship without that common knowledge means not just starting from square one, but moving back to square zero. With historical accuracy as our goal, we must unlearn the things we have learned from TV, movies, fencing, SCA and Eastern martial arts.

To study historical swordsmanship, we have to focus on learning the real techniques preserved in the historical manuals, which reveal themselves through training. And since we’ll never have the chance to try them in combat, we need an effective method of practice and sparring that checks the effectiveness of our technique against a determined opponent.

The need for safety

That’s where safety rears its ugly head. The only way to be confident that a technique works is to use it effectively against a determined, skilled opponent in a life or death struggle. When you try to simulate this reality as closely as possible, you’re essentially weighing safety in one hand and realism in the other. You’ve got to strike a balance as far in the favor of realism as you can without sacrificing safety.

If you begin with real combat as your “ideal,” the first obvious safety measure is to use blunted weapons. The next measure is to use both headgear (fencing mask) and gloves – though there is precedent for “scholar’s privilege” which is an agreement not to thrust to the head, The Order of Lepanto requires both men to have achieved Knight Scholasticus ranking before it can be invoked. But a blunted weapon isn’t necessarily a safe one, which means that participants must also exercise proper control. Strikes must be carried out with enough speed to be effective in a real confrontation and yet contact must also be controlled enough to keep your partner safe.

Simulating the sword

In the medieval and Renaissance period, swords were not mass-produced to some pre-determined standard. Looking back, it is impossible to define the specifications of a longsword versus a cut-and-thrust sword beyond generalities. Therefore, we cannot say for certain that a specific sword accurately simulates the handling of all swords of a similar type.

One of the key issues is that virtually no modern maker has their hand-forged pieces tested for durability in warding off the full force blows of other sharp blades, nor do they go around hitting soft and hard armors full force. So much work and effort has gone into their pieces that they do not want to see them damaged. Further, customers who have spent a lot of money are not about to damage them doing the same either. Most every maker and every consumer does minimal work to evaluate a blade to the point of destruction. They then base their future impressions of other swords upon that small experience.

Another problem is that every sword can be unique. Even ones that match the same general geometry and form can vary considerably. When it comes to replicas, unfortunately, there are just so many different elements to miss and crucial factors to get wrong that the bad samples seem to outnumber the good ones by a good bit. Just getting the general shape and weight correct, then using quality steel that’s been properly tempered isn’t enough.

When you pick up most any sword, you can make an instant decision as to whether or not it “feels” good. However, without manipulating that sword with proper motion and energy, this is a very shallow assessment. There is a combination of factors that go into making a sword really stand out as a real weapon. While these are not evident through holding a piece in your hand or moving it through empty air, they become obvious it’s wielded with the requisite force and energy needed to strike effective blows against a test target combined with practice in warding off forceful strikes. This is where you see whether a weapon holds up and how well it maneuvers for whatever combat actions it was originally designed.

Nevertheless, we know from other examples that simulation can be a valid form of training – police live-fire combat ranges and pilot training programs make similar trade-offs without losing their effectiveness as tools. As long as there is an awareness of the nature of the simulation, and the aspects of combat that the model doesn’t accurately portray, the use of simulation in training is a plus.

Two Three-Legged Stools

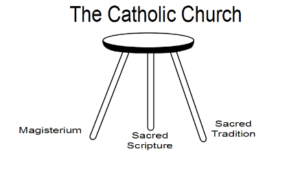

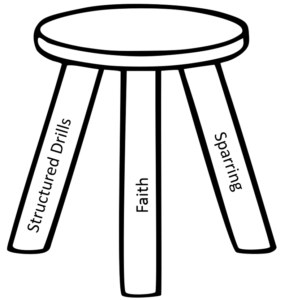

Ironically enough, fighting it out with the real weapons is the most ineffective method of training of all, since only one participant gets the opportunity to learn from his mistakes. To learn historical swordsmanship more effectively, we need a system that uses a “triangulating” approach – combining different aspects into a cohesive system of the sword and faith. Much like the three-legged stool of the Church – Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium – without which the faith cannot stand, the studies of the Order of Lepanto are three-legged as well.

Ironically enough, fighting it out with the real weapons is the most ineffective method of training of all, since only one participant gets the opportunity to learn from his mistakes. To learn historical swordsmanship more effectively, we need a system that uses a “triangulating” approach – combining different aspects into a cohesive system of the sword and faith. Much like the three-legged stool of the Church – Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium – without which the faith cannot stand, the studies of the Order of Lepanto are three-legged as well.

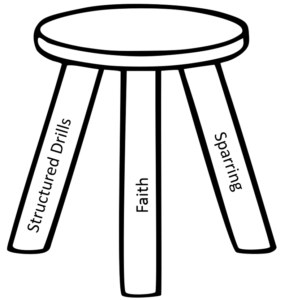

The first leg of our training is structured drills, undertaken with either a wooden “waster” or a blunted steel. These weapons have the weight and appearance of the real thing, and they have some of the same handling characteristics, such as a tapering blade and a discernible edge. They teach precision and finesse. We review drawings and descriptions of the actions in historical documents and then work to understand the motion and dynamics being described. This first takes places at slow speed, before building up to a medium pace, with the overall intent of creating muscle memory of the action so that it can be employed with little thought. Drills in this category include fuhlen (or feeling), where the practitioner learns to feel his opponent’s sword and read his intent, in addition to master stances, master cuts, and counters.

Taken alone, structured drills with blunt replicas is not an effective method for learning the martial aspect of historical swordsmanship. The second leg of our stool is sparring (referred to as “free play” by some). In sparring, we look to deliver solid, forceful blows without injuring an opponent, which allows a full-body target – an essential for realistic combat training. In sparring we put the actions that are practiced in drills to use in an adversarial (yet friendly) situation. The more realistically sparring is conducted, the more it sharpens reflexes, develops perception, teaches adversarial counter-timing, explores spontaneous tactics, conveys the skill of deceiving without being deceived, and lets the student try things that end up with them either getting whacked or not, but in the process not being maimed or killed.

Our third, and final, leg is the Catholic perspective. In this area of our studies, members are actively reading period writings by saints such as Ignatius of Loyola, and looking to understand how the martial arts of that period shaped their understanding of the faith. We look to leverage our knowledge of sparring technique and weapons drills towards a deeper understanding and appreciation of spiritual warfare. Sharpened reflexes, detailed perceptions, and being able to respond spontaneously are all skills that are sharpened with martial arts and critical to the spiritual battles everyone will face. We also explore this area though prayer – our groups are required to open and close each practice in group prayer. The act of practicing martial arts servers to bring our members closer together and when combined with the positive spiritual experience shared prayer, we grow towards a closer brotherhood.

Taken as a whole, this system “triangulates” true skill by approaching practice from several different angles. When you add to this our insistence on test cutting (and thrusting) with sharp weapons, you get a fairly complete understanding of both historical swordsmanship as distinct skills and how that skill shaped the faith of the historical swordsman.

Don’t miss the focus

This is not a question of condemning fencing, the SCA, or any other group. You don’t have to look hard to see that there is a difference between what they do and what The Order of Lepanto does. The mistake people make is to look at one or two aspects of what we do and missing the bigger picture. He saw a part of the picture, but not the whole.

The thing that separates what The Order of Lepanto does from sport fencing, groups such as the SCA – and most any other program you compare it to – is that the purpose of our method is to produce skilled combatants. But there is another dimension too – because while there are other groups whose sole focus is historical combat, only The Order of Lepanto looks to grow beyond pure combat and help to build faith-filled Catholic men, who can use their martial skill in the test of spiritual warfare. In that vein, we do not sponsor competitions or anoint kings or put on performances. Our focus is narrow and concerns itself with than the effective use of historical weapons as a martial art and building a strong Catholic faith. You must not look at any aspect of the Order of Lepanto training system as a stand-alone piece or an end unto itself. As our introduction pointed out, no one involved in our group is concerned about learning to fight well with wooden swords or learning to fight well with padded swords. What we are concerned about is learning to fight well with real, sharp swords and with a real prayer life. All of these simulators are tools to help accomplish our goal, and together, they combine to offer a very effective system.

Here are The Order of Lepanto’s guidelines employed as general rules of thumb for sparring:

- Situational Awareness = Maintaining good edge alignment and targeting

- Purpose = striking with a degree of force within range to achieve actual contact; must be done in a way that has proper motion to simulate the inertia of a real blow

- Control = not hitting too hard or too fast to prevent injury, striking the selected target

- Time-on-Target = connecting with a sufficient interval of time whereby the weapon makes contact in order to simulate the energy that would have impacted or penetrated

Before we get into how a martial arts practitioner combines faith and love with the art, we should talk a bit about what martial arts really are. First, there is a misconception that true martial arts are Asian; however, the truth is that the term “martial arts” is a European term that refers to the “arts of mars” – the Roman god of war. Therefore any system of self-defense is a “martial art”, including one’s which use modern weapons. The Europeans in the late-Medieval and Renaissance periods created a comprehensive system of self-defense that was documented in books – some of those were written by priests and monks, and many others written lay Catholics. As with any other skill, self-defense systems can be used for good or evil depending on the person.

Before we get into how a martial arts practitioner combines faith and love with the art, we should talk a bit about what martial arts really are. First, there is a misconception that true martial arts are Asian; however, the truth is that the term “martial arts” is a European term that refers to the “arts of mars” – the Roman god of war. Therefore any system of self-defense is a “martial art”, including one’s which use modern weapons. The Europeans in the late-Medieval and Renaissance periods created a comprehensive system of self-defense that was documented in books – some of those were written by priests and monks, and many others written lay Catholics. As with any other skill, self-defense systems can be used for good or evil depending on the person. define love? Since you, the reader, are English-speaking you realize that English uses “love” to describe many different feelings. For instance, “I love pizza” has a totally different meaning than “I love my wife”, which describes a different feeling from “I love my parent/child/sibling.” In other languages that catch-all word of love, gets translated into separate words to more accurately describe the feeling. In Greek (which is what much of the New Testament was written in) we would use Agape, Phileo, Storge, and Eros in place of the English “love.” You can find good explanations at many places on the internet, so I won’t delve into that here (this article has a short explanation). To sum it up, though, we would say:

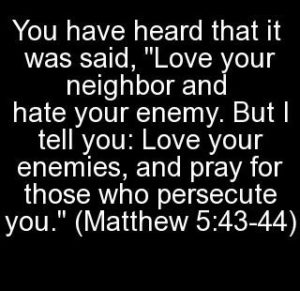

define love? Since you, the reader, are English-speaking you realize that English uses “love” to describe many different feelings. For instance, “I love pizza” has a totally different meaning than “I love my wife”, which describes a different feeling from “I love my parent/child/sibling.” In other languages that catch-all word of love, gets translated into separate words to more accurately describe the feeling. In Greek (which is what much of the New Testament was written in) we would use Agape, Phileo, Storge, and Eros in place of the English “love.” You can find good explanations at many places on the internet, so I won’t delve into that here (this article has a short explanation). To sum it up, though, we would say: covered to our initial question – “How does a Catholic martial artist love his enemies?” The answer seems to be clear – although we do not show eros, phileo, or storge love to our enemies, we can show agape love. The essence of agape love is an exercise of the will, causing an action where we choose to do something that is in the best interest of another. A practitioner of a martial art who steps in to stop an unjust aggressor from harming an innocent person shows that innocent person agape love. The act of protecting another, while subjecting oneself to possible harm clearly meets that agape definition. If our fictitious doer-of-good-deeds only uses the amount of force necessary to stop the attack (even if that might require deadly force), you could make the argument that agape love was shown to the attacker through restraint. However as a further action, our protector in the story could offer forgiveness to the attacker and pray for his or her conversion (once the danger of aggression has been stopped) and show an even greater example of agape love.

covered to our initial question – “How does a Catholic martial artist love his enemies?” The answer seems to be clear – although we do not show eros, phileo, or storge love to our enemies, we can show agape love. The essence of agape love is an exercise of the will, causing an action where we choose to do something that is in the best interest of another. A practitioner of a martial art who steps in to stop an unjust aggressor from harming an innocent person shows that innocent person agape love. The act of protecting another, while subjecting oneself to possible harm clearly meets that agape definition. If our fictitious doer-of-good-deeds only uses the amount of force necessary to stop the attack (even if that might require deadly force), you could make the argument that agape love was shown to the attacker through restraint. However as a further action, our protector in the story could offer forgiveness to the attacker and pray for his or her conversion (once the danger of aggression has been stopped) and show an even greater example of agape love. I have been attending men’s conferences and local parishes recently in order to talk to men about the Order of Lepanto. There is, invariably, a lot of excitement when we show sparring (either live or in videos) and as interest builds the question of equipment and cost comes up. I have prepared this short article to try and answer the question of what is needed, divided into must have, good to have, and nice to have.

I have been attending men’s conferences and local parishes recently in order to talk to men about the Order of Lepanto. There is, invariably, a lot of excitement when we show sparring (either live or in videos) and as interest builds the question of equipment and cost comes up. I have prepared this short article to try and answer the question of what is needed, divided into must have, good to have, and nice to have. moisture wicking pants and shirt, though we do emphasize that they need to have no logo (or a smallish logo). There is also the option of an historical uniform – any medieval or renaissance swordsman shirt in white or natural would be acceptable. As for historical pants, you can also substitute knee breeches or long pants. Shorts can be worn in hotter climates.

moisture wicking pants and shirt, though we do emphasize that they need to have no logo (or a smallish logo). There is also the option of an historical uniform – any medieval or renaissance swordsman shirt in white or natural would be acceptable. As for historical pants, you can also substitute knee breeches or long pants. Shorts can be worn in hotter climates. of Lepanto, so we train for good control and require some safety devices. The first requirement is that everyone wears a fencing mask while sparring with any kind of weapon. You can get a fencing mask fairly inexpensively ($50) and we have a couple of vendors that we recommend here.

of Lepanto, so we train for good control and require some safety devices. The first requirement is that everyone wears a fencing mask while sparring with any kind of weapon. You can get a fencing mask fairly inexpensively ($50) and we have a couple of vendors that we recommend here. practitioners need to have a bit of finger protection because our hands are vital to our jobs. What we want to avoid here is overly padded gloves that distort the handling and feeling of the sword. A set of leather gloves, or the mechanics gloves with the rubber pads work nicely. We require gloves for our transitional squires and first level knights, more experienced knights can opt for “knight’s privilege” (historical training privilege) though it not recommended. ($25)

practitioners need to have a bit of finger protection because our hands are vital to our jobs. What we want to avoid here is overly padded gloves that distort the handling and feeling of the sword. A set of leather gloves, or the mechanics gloves with the rubber pads work nicely. We require gloves for our transitional squires and first level knights, more experienced knights can opt for “knight’s privilege” (historical training privilege) though it not recommended. ($25)

The first thing we’ll cover in this section is a blunt steel sword. This is first because it is the most visible sign of a more experienced practitioner. There are only a few companies that make good blunt swords for sparring – Albion, Regenyei, Lutel, and Hanwei. Prices range from $200 to $500 for these swords. The best of these are the swords from Albion, while the Hanwei swords are the most affordable. Also, be aware that the Hanwei Tinker-Pearce comes with a square edge that you must file down for safety.

The first thing we’ll cover in this section is a blunt steel sword. This is first because it is the most visible sign of a more experienced practitioner. There are only a few companies that make good blunt swords for sparring – Albion, Regenyei, Lutel, and Hanwei. Prices range from $200 to $500 for these swords. The best of these are the swords from Albion, while the Hanwei swords are the most affordable. Also, be aware that the Hanwei Tinker-Pearce comes with a square edge that you must file down for safety.

Unlike sixteenth century swordsmen, today’s student of the sword will, most likely, never have the opportunity to put his skill to the ultimate physical test. Even so, we want to develop true martial skill in the art. By then translating the lessons to our spiritual life, we will be more prepared for the real-life tests our faith will have to endure. So the approach we have developed at the Order is true to martial skills, martial heritage, and orthodox Catholic teaching. It is certainly one of the most complex, and it offers something more than what is generally available in Western swordsmanship. Let’s look at what the Order of Lepanto’s method of teaching historical swordsmanship and spiritual growth is all about.

Unlike sixteenth century swordsmen, today’s student of the sword will, most likely, never have the opportunity to put his skill to the ultimate physical test. Even so, we want to develop true martial skill in the art. By then translating the lessons to our spiritual life, we will be more prepared for the real-life tests our faith will have to endure. So the approach we have developed at the Order is true to martial skills, martial heritage, and orthodox Catholic teaching. It is certainly one of the most complex, and it offers something more than what is generally available in Western swordsmanship. Let’s look at what the Order of Lepanto’s method of teaching historical swordsmanship and spiritual growth is all about. you increasing your knowledge of the faith. Many people today have been left with a teenage understanding of the faith because that is where the traditional religious education program stopped. The Order of Lepanto aims to build an adult understanding of your catholic faith and help you to grow in that faith.

you increasing your knowledge of the faith. Many people today have been left with a teenage understanding of the faith because that is where the traditional religious education program stopped. The Order of Lepanto aims to build an adult understanding of your catholic faith and help you to grow in that faith. life or death context. Even if the nearest thing at hand when your house is broken into is your trusty longsword, the odds of your intruder also being a swordsman are slim to none.

life or death context. Even if the nearest thing at hand when your house is broken into is your trusty longsword, the odds of your intruder also being a swordsman are slim to none.

Ironically enough, fighting it out with the real weapons is the most ineffective method of training of all, since only one participant gets the opportunity to learn from his mistakes. To learn historical swordsmanship more effectively, we need a system that uses a “triangulating” approach – combining different aspects into a cohesive system of the sword and faith. Much like the three-legged stool of the Church – Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium – without which the faith cannot stand, the studies of the Order of Lepanto are three-legged as well.

Ironically enough, fighting it out with the real weapons is the most ineffective method of training of all, since only one participant gets the opportunity to learn from his mistakes. To learn historical swordsmanship more effectively, we need a system that uses a “triangulating” approach – combining different aspects into a cohesive system of the sword and faith. Much like the three-legged stool of the Church – Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition, and the Magisterium – without which the faith cannot stand, the studies of the Order of Lepanto are three-legged as well.

I was reading an

I was reading an  the faithful to pray the Rosary for intention of victory, the commander of the Catholic forces ordered his men to pray the Rosary on the morning of battle before the fighting began, and finally the men carried their Rosaries into the battle. Indeed, the prayers of the faithful had been heard, but without the “yes” of those men, without their dedication to fighting against evil and for good the prayers could not have been answered. That very Catholic combination of works in faith is what made the victory possible.

the faithful to pray the Rosary for intention of victory, the commander of the Catholic forces ordered his men to pray the Rosary on the morning of battle before the fighting began, and finally the men carried their Rosaries into the battle. Indeed, the prayers of the faithful had been heard, but without the “yes” of those men, without their dedication to fighting against evil and for good the prayers could not have been answered. That very Catholic combination of works in faith is what made the victory possible. happens next in the story is just as important – once Frodo realized that the immediate danger had passed, he let down his guard. This happens to us too. We turn to God in the dark times, yet as soon as the situation improves we go back to ignoring Him (sometimes not even bothering to say thank you for His help). When we turn from prayer and action too soon, or for too long, the evil that had threatened, returns. In the story Shelob sneaks into a hiding place and sets a trap. Her next attack deprives Frodo of his phial and sword – unable to pray or to defend, he is quickly defeated. How often this occurs to us. We leave our prayer life and our taken by surprise by Satan and sin. Without the protection offered by the spiritual graces, we are quickly subdued and taken. If we are lucky, we have a friend like Samwise Gamgee who will pray for us, defend us, and rescue us when we are in the deepest need.

happens next in the story is just as important – once Frodo realized that the immediate danger had passed, he let down his guard. This happens to us too. We turn to God in the dark times, yet as soon as the situation improves we go back to ignoring Him (sometimes not even bothering to say thank you for His help). When we turn from prayer and action too soon, or for too long, the evil that had threatened, returns. In the story Shelob sneaks into a hiding place and sets a trap. Her next attack deprives Frodo of his phial and sword – unable to pray or to defend, he is quickly defeated. How often this occurs to us. We leave our prayer life and our taken by surprise by Satan and sin. Without the protection offered by the spiritual graces, we are quickly subdued and taken. If we are lucky, we have a friend like Samwise Gamgee who will pray for us, defend us, and rescue us when we are in the deepest need. which will keep you burning the calories and losing weight. Additionally, as previously discussed, you will be building muscle mass, which will also help improve your metabolism and allow your body to burn more calories at a rapid pace.

which will keep you burning the calories and losing weight. Additionally, as previously discussed, you will be building muscle mass, which will also help improve your metabolism and allow your body to burn more calories at a rapid pace. authors and from each in other about spiritual warfare and how to apply the lessons of European martial arts to that spiritual war. We also actively engage in group prayer and stress the importance of personal and family prayer time each day. In combining faith and sparring, we build a bond of brotherhood between the men in our groups. This bond allows us to offer each other fraternal correction and support from a position of trust and respect. We truly help each other to be better men.

authors and from each in other about spiritual warfare and how to apply the lessons of European martial arts to that spiritual war. We also actively engage in group prayer and stress the importance of personal and family prayer time each day. In combining faith and sparring, we build a bond of brotherhood between the men in our groups. This bond allows us to offer each other fraternal correction and support from a position of trust and respect. We truly help each other to be better men. The participation in martial arts, while not for every man, offers great benefits to you in your physical, metal, and spiritual well-being. The Order of Lepanto is on a mission to get men involved and connected with each other and the Church, while building their courage and confidence.

The participation in martial arts, while not for every man, offers great benefits to you in your physical, metal, and spiritual well-being. The Order of Lepanto is on a mission to get men involved and connected with each other and the Church, while building their courage and confidence. As many of us are painfully aware, there has been a lack of evangelization directed towards men. Men are not hearing what they need from the pulpit and there have been few resources to help in our faith journey. The good news is that this has been changing in recent times, The Order of Lepanto is one of the resources aiding in the shift along with many other fine Catholic men’s blogs. But for many, the call to arms from the hierarchy of the Church was a missing piece of the puzzle.

As many of us are painfully aware, there has been a lack of evangelization directed towards men. Men are not hearing what they need from the pulpit and there have been few resources to help in our faith journey. The good news is that this has been changing in recent times, The Order of Lepanto is one of the resources aiding in the shift along with many other fine Catholic men’s blogs. But for many, the call to arms from the hierarchy of the Church was a missing piece of the puzzle.

Much has been written about a lack of men in the faith. The truth is that many men see Catholicism and Christianity as a feminine pursuit, even those who are believers. The truth, however, is strikingly different. God created masculinity just as much as He created femininity, and both must have a place in the Church. The masculine spirit thrives on challenge, adventure, and truth. We want to hear God’s teaching about the right way to do things and be personally challenged to achieve that lofty goal. The true masculinity that God has called us to is not the one where we watch sports all day on Sunday and drink beers with the guys; it is a vibrant and strong relationship where we strive to live God’s calling as spiritual leader and that of beloved son of the Almighty. While there is nothing inherently wrong with those activities, when they are pursued without regard to faith and family our lives become focused on the wrong goal. Too many men are missing from the pews today, and that is just a visible sign of the deeper problem: Too many men are absent from their roles as spiritual leader of their homes. How can we attract men back to the faith? My proposition is that a strong, faith-based martial arts program is one avenue to accomplishing this.

Much has been written about a lack of men in the faith. The truth is that many men see Catholicism and Christianity as a feminine pursuit, even those who are believers. The truth, however, is strikingly different. God created masculinity just as much as He created femininity, and both must have a place in the Church. The masculine spirit thrives on challenge, adventure, and truth. We want to hear God’s teaching about the right way to do things and be personally challenged to achieve that lofty goal. The true masculinity that God has called us to is not the one where we watch sports all day on Sunday and drink beers with the guys; it is a vibrant and strong relationship where we strive to live God’s calling as spiritual leader and that of beloved son of the Almighty. While there is nothing inherently wrong with those activities, when they are pursued without regard to faith and family our lives become focused on the wrong goal. Too many men are missing from the pews today, and that is just a visible sign of the deeper problem: Too many men are absent from their roles as spiritual leader of their homes. How can we attract men back to the faith? My proposition is that a strong, faith-based martial arts program is one avenue to accomplishing this. Catholicism. The eastern martial arts (Karate, Tae-kwon do, etc.) are based in eastern mysticism and spirituality which are not entirely compatible with the Christian faith. Many modern people think only of eastern martial arts, but there is a rich history of martial arts in Western Europe, too. The Europeans, with their Catholic faith, created their own martial arts which were (and still are) quite effective. This system covered the use of weapons as well as unarmed confrontations, and many parts were written down so that today, several hundred years later, we can know how many of their techniques worked. Not only are western martial arts effective and compatible with Catholicism, they actually offer the practitioner unique and valuable insights into the spiritual journey and answering the calling of men by God.

Catholicism. The eastern martial arts (Karate, Tae-kwon do, etc.) are based in eastern mysticism and spirituality which are not entirely compatible with the Christian faith. Many modern people think only of eastern martial arts, but there is a rich history of martial arts in Western Europe, too. The Europeans, with their Catholic faith, created their own martial arts which were (and still are) quite effective. This system covered the use of weapons as well as unarmed confrontations, and many parts were written down so that today, several hundred years later, we can know how many of their techniques worked. Not only are western martial arts effective and compatible with Catholicism, they actually offer the practitioner unique and valuable insights into the spiritual journey and answering the calling of men by God.